You’d think having staff throw a senior accountant into a swimming pool on her birthday would be more likely to set off an HR firestorm than promote a great workplace culture.

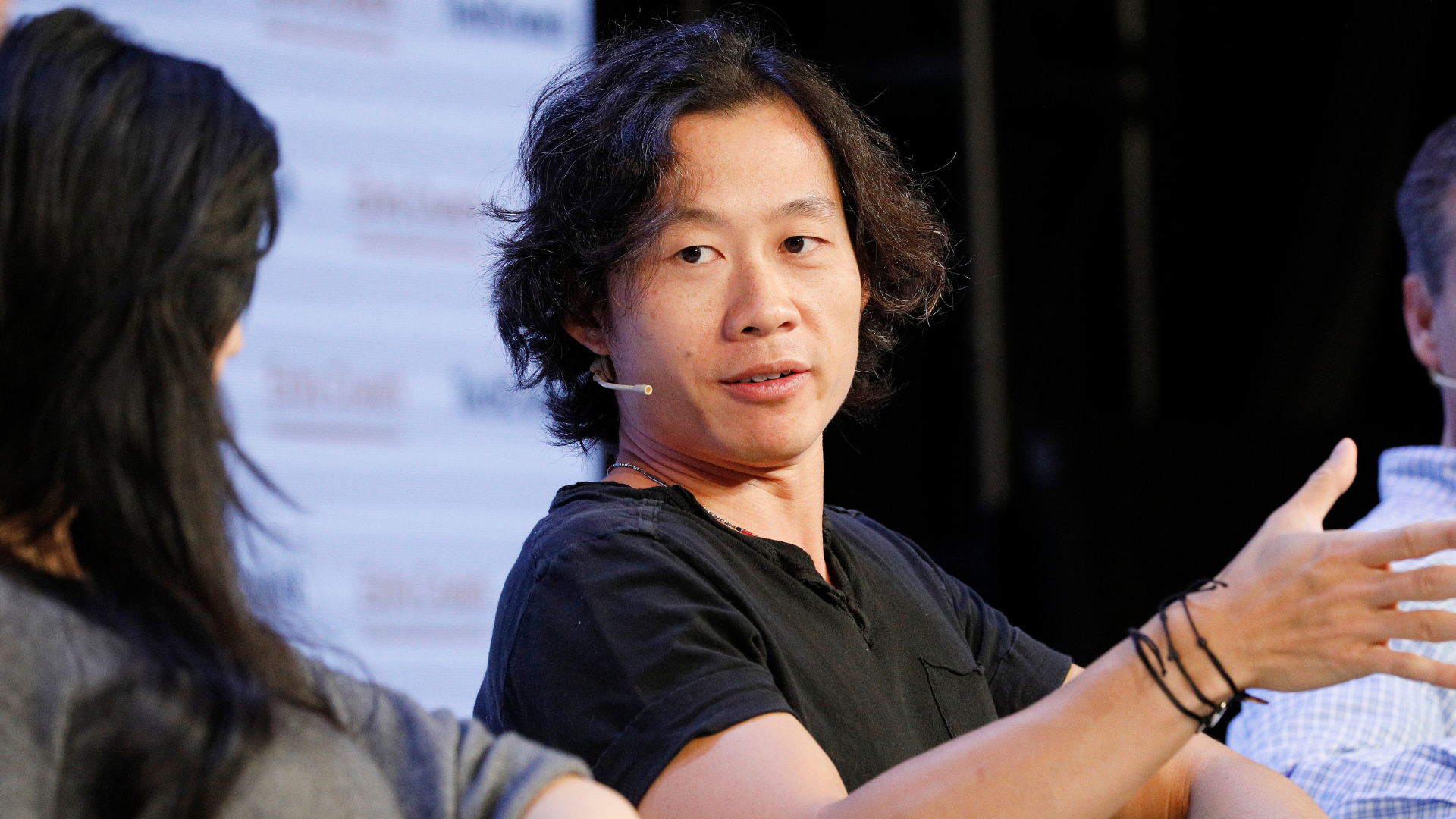

But for Moses Lo’s payments platform Xendit, the birthday dunking tradition was just one small, if unconventional, way to transfer the dynamic, meritocratic approach of Silicon Valley to the more hierarchical cultural context of Southeast Asia.

“We’re trying to exemplify this culture of ‘everyone is equal.’ We want good ideas to win, not just [take precedence] because you’re older,” the Xendit co-founder and CEO tells MONIIFY’s Money Moves.

To build a culture where everybody felt empowered to contribute meant scrapping honorifics. It meant speaking English, which lacks the built-in deference to seniors common in many languages. And yes, it meant insisting that everyone got soaked on their birthday.

That overall approach has paid off for Xendit, the Indonesian fintech unicorn that’s been ambitiously expanding across Southeast Asia, bringing its digital-payment systems to the Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam. It has undergone several pivots since it was launched in 2015 and has faced challenges including layoffs and restructuring. Now, it processes more than $50 billion in payments annually.

The company’s rapid success owes a lot to Lo’s own cosmopolitan background: he’s half-Indonesian, half-Malaysian, Singapore-born, Aussie-accented.

The former strategy consultant did his undergrad studies in Sydney, and an MBA at UC Berkeley before moving on to Silicon Valley. There, Xendit became the first Indonesian company to be accepted into the prestigious Y Combinator startup accelerator, which has spawned successes like Airbnb, Stripe, Coinbase, DoorDash and Dropbox.

“The opportunity to be a local and a foreigner, wherever you are, brings pretty fun perspectives,” he says. “When you have to adapt all the time, you can try to bring the best of both worlds and say: ‘Hey, what works? How do we blend East and West?’”

Crucial in helping Lo get to where he is today has been the advice of successful mentors – people who have been there before and learned a thing or two. We’re talking names like Twitch co-founder Justin Kan, or Shazam co-founder Philip Inghelbrecht – although Lo says they’ve probably never defined the relationship in those terms (all part of the secret of wooing them – more on that later). In turn, Lo is pretty generous in sharing his own advice during an hour-long interview with Money Moves’ Muhammed Mekki.

Here are three takeaways from the conversation:

- On mentors. Saying to someone “Will you be my mentor?” like you’re asking them to a dance isn’t really the move. Lo’s trick: if he meets someone who might have a useful perspective, he’ll ask for advice. The crucial part comes three months later, when he’ll update them on how their advice worked – or didn’t – then ask a follow-up question. Keep it going, and voila: you’ve got yourself a mentor.

- On fundraising. “If you want money, ask for advice, and if you want advice, ask for money,” says Lo. By pulling together a network of mentors and advisers who are engaged in your startup and have watched its progress, you’re essentially building a pipeline of potential investors when it’s time to look for funding.

- On thinking big. At Berkeley, Lo was pitching business ideas to an adjunct professor when he cut him short. “Stop,” the professor said. “If your idea isn’t worth $1 billion, don’t talk to me.” Lo was taken aback, but the interjection triggered a mindset shift: maybe he could come up with a $1 billion idea. Eventually he did.

Muhammed Mekki: Xendit was the first Indonesian startup to join the famous Y Combinator startup accelerator. How did you manage that?

Moses Lo: It was fun breaking some bamboo ceilings. For us, we were lucky. I was studying in Berkeley at the time, so I think that helped.

We were lucky to get Justin Kan as one of our interviewers. He, it turns out, has some family in Indonesia. So, when we said we want to build for Southeast Asia, he actually understood what that meant.

We had traction. We were growing 30% month on month. And the ability to prove that this is a real business opportunity. I think that helped.

Lastly, being able to get other YC founders that gave us good advice on how to get in, and mentor us, and do the practice YC interviews. That was all very helpful.

- Mekki: Today, Sam Altman is famous as the CEO of OpenAI, but during my time in Silicon Valley, he was known for his role in leading Y Combinator and overseeing the birth of startups. I hear you had a challenging first interview with him.

We had the unfortunate experience of having two YC interviews. Sam Altman interviewed us for 10 minutes the first time, and he asked us all these questions – as a fintech guy, as a Bitcoin guy. About Bitcoin and what we knew and understood. We obviously were shameful compared to him.

But, lucky for us, he was able to say: “Hey, we won’t deny you straightaway. We’ll do a second interview.” In that second interview, about four hours later, we changed our tactics pretty significantly. [It was] great to have Justin Kan interview us. I think through that then, we were pulled in.

- Mekki: You obviously took a lot from being in Silicon Valley, but then you’ve built your business in Southeast Asia. Were there any particular approaches you’ve tried to bring over and implement in this part of the world?

[Our] approach has been, OK we’re from the East. We managed to, in my case, get to study in the West. How do we blend the best of both worlds? How do we build what we want?

What we don’t like about how things are here in Asia is hierarchy. It’s not the best idea wins. It’s the oldest person wins, or whoever has the most senior title wins. We thought that’s not the best way to run something that’s trying to grow quickly.

The other thing is Southeast Asia is very passive aggressive. We don’t get into direct conversations. Sometimes it takes so much longer to figure out what it is that people are really saying. It also means that if we have a mix of cultures, whoever has a louder culture tends to overpower conversation.

Read more: Meet the part-time DJ, full-time tycoon who wants to make you richer

So, we very much brought that Silicon Valley idea of meritocracy. And we kind of fixed both problems through a bunch of different tools.

For us, it was: “OK, let’s change to English.” We refused to use titles inside the organization and there’s hierarchy in the language in this part of the world too. But we get rid of all this. You can’t call someone by their senior title like “Mr” or “Sir” – just by their names. English helped with that.

- Mekki: It’s got to be a challenge, though, to build a culture that’s so different from what’s going on outside the walls of the organization.

I think we had to exemplify it as a leadership group.

As leaders, we would never talk to each other with titles. And when we hired senior people, older people in our case, we were very clear on what we expected and what we wanted – and they bought in on that.

For example, we had this crazy thing that we don’t do anymore. But in the early days on your birthday, you got thrown in the pool, because we were … working out of homes. People brought a change of clothes knowing they’re going in.

The first time we had our senior accountant. She’s an older person within the organization, but we’re like: “Hey, we’re going to throw you in the pool, too, because we’re trying to exemplify this culture of everyone is equal.”

She’s like: “I’m fine with that. Let’s do it.”

- Mekki: What tips do you have on building those relationships with investors and convincing them to jump in on something risky?

I’d never start the relationship by asking for money. The goal was really to seek their advice, seek their counsel on how to build a business.

I’d be very clear. “I’m not looking for money now because I genuinely want advice.” And then over time I’ll prove to you what I can do. So that when the time comes for me to say, “Hey, we’re thinking about raising a round,” it’s already a very easy decision – yes or no – for the person on the other side of the table.

We’re all human, so investing a little bit out of FOMO. So how do you drive that process where people realize “I want to be in this round right now, and I want to say yes earlier rather than later?”

I think those … principles are pretty helpful in constructing fundraising and realizing it happens years before you ever ask for money.

- Mekki: You’ve taken a somewhat traditional path into leading a large startup: a top school like Berkeley, being a strategy consultant, going to YC. To what extent do you feel that that’s a prerequisite?

I would care more about the experiences to try to learn, versus the badges to have on a resume. For me, the joy of going to the US or Silicon Valley was to learn: “how do startups get built and get the right mindset?”

Coming from a small country like Australia, with tall poppy syndrome – excessively promoting your own achievements and opinions – and a bunch of cultural context, I think going to America and learning what is possible mattered a lot.

I’ll give you an example [about] an adjunct professor at Berkeley. I sat him down for office hours and I came to him with a bunch of ideas and five minutes in[to] the conversation, he stopped me.

He said: “If your idea isn’t worth $1 billion, don’t talk to me.”

At first I was like: “This is a massive reprimand. I didn’t think of a good enough idea.” But then I also thought, hang on, that means he accepted the meeting and expected I would show up with only billion-dollar ideas.

In that way, he’s the first person to ever believe I can come up with a $1 billion idea. That’s one of many mindset changes that happened when I was in Silicon Valley.

[It’s] having the exposure [to] people who built billion-dollar businesses who can say “This is how I did it. These are the problems I faced.” Especially – this is a bit unique to Silicon Valley – how open people are with their war stories, with the downs. I think so much of Asia is presenting a certain front and saving face. But there, people are just being open.

I’ve learned a lot from people here [in Asia] too. North Asia has a ton of great founders as well.

- Mekki: Finally, let’s imagine you’re established in your first job and you’ve pulled together your first $10,000 of investable money. How do you spend it?

There’s a couple of things that I think are really interesting. One is, how [do] the real hard parts of the economy get eaten more and more by AI and software? And then how does that interplay with geopolitics?

So, for example … rare earth metals. These are really important for anything we care about in our lives – electronics, semiconductors, cameras, phones.

But the supply chain is very constrained and run by very few economies in the world. Depending on where you sit in this multipolar set of superpowers, there’s easy access, or not easy access, to rare earth metals.

So something like that where – like in the US, for example, there’s only one mine for rare earth metals in the whole country, but it’s so important to the supply chain – something like that would be kind of an interesting place to figure out: “Hey, where’s a bet I could make that is technology-enabled? But a … real world use case that is going to be hard to replicate.”

I love the idea of, in the gold rush, the company that we remember now is Levi’s – not the people who hunted for gold, [but] the guys making the pants.

`I would be looking at, let’s say I picked this idea of mining in whatever country, then say: which companies are enabling whoever wins – whoever’s going to win that game – to be able to operate.

What is the equivalent of Levi’s jeans?