There’s a new commodities supercycle coming and it’s driven by years of underinvestment in mining.

The last major commodity cycle is some 40 years behind us now. Few investors active today experienced it. Warren Buffett is the famous exception. So take note: Today, the Oracle of Omaha is firmly on the buy side.

Cycles, of course, are a constant. That’s because, as economists like to remind us, the best remedy for high prices is high prices and the best remedy for low prices is low prices. What this means, essentially, is that when commodity prices are high, companies flock to those handsome profits and invest more money in the sector. Supply goes up and prices eventually go down. If prices are low, logically, there’s less investment and some weaker players will go out of business. Supply falls and prices then rise.

The reason we are on the brink of a giant cycle today is because there’s been massive underinvestment in commodities that’s lasted for a decade or more.

That’s partly driven by the changing energy lanscape. Hydrocarbons prices have dropped significantly since 2010 as American shale oil and gas entered the market, increasing supply. Prices of most metals were also low, so there were few incentives to invest. Add to that the fact that many big oil and mining giants had overspent and overpaid for certain assets during the previous boom, and it’s not so surprising that investment has been at historic lows for a while. The transition to clean energy means that investments in fossil fuels and mining are not as popular as they were. So even with rising prices, we don’t see money flowing into these sectors. Quite the contrary.

What about the demand side?

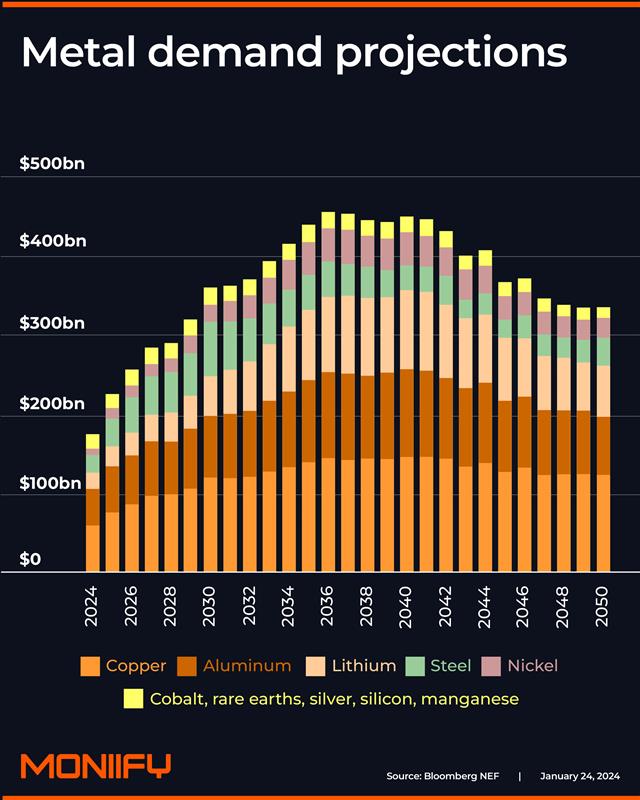

Demand is very difficult to predict in the short term because it depends so much on the economic cycle. But in the slightly longer term, the trends are clear. The chart below shows demand for certain metals over the next few years.

So much is changing, though, that it’s not easy to predict how things will play out. Take battery metals, for example. Today, cobalt is needed in batteries, but no one knows whether this will still be the case in a few years. It’s very difficult to predict what the batteries of the future will look like. The same goes for lithium; it’s very difficult to recycle and predictions suggest we’ll need much more than we use today. That is until a method is found to replace lithium. Remember that, at one point, aluminum was more expensive than silver because there was no good way to extract it from bauxite.

We are most confident when it comes to copper demand though. Copper will still be needed if you want to get electricity from point A to point B, something that will come in handy with the electrical revolution.

When we look back at the next 10 years, we may see them not only as a period of shortages but possibly also of shocks. We will not then be talking about oil shocks, as in the 1970s, but metal shocks. In a market that promises to be so tight, any supply disruption – due to war, revolution, or disaster – could cause enormous price swings.

It’s no coincidence that more and more countries are calling not only rare earth elements but also copper a strategic commodity. They will try to secure supply — and copper supply is concentrated in about six countries. Governments in Chile and Peru are already looking to take more control of lithium production within their borders and let the profits flow back to their people. Why shouldn’t they do the same for copper?

Are we looking at world where an OCEC (Organization of Copper Exporting Countries) will have as much influence as today’s OPEC.

Is gold the ultimate commodity?

Few investments capture, divide, and confuse hearts and minds as much as gold. Every day, we speak to diehard believers and even more strident detractors. The latter, including Warren Buffett, consider gold a barbaric relic at best. Yet there are as many reasons to invest in gold as there are buyers.

Two very obvious ones are protection against inflation and just about any other calamity. That protection against inflation exists but it really only applies in the very long term. Studies suggest that with the amount of gold it took to buy a toga in Roman times, you can buy a nice, sleek suit today. The statement also holds true over periods of more than 50 years. But there are quite a few periods of 20 years or more when gold does not offer proper protection, or even offers poor protection, against the general rise in price levels.

A third and possibly more important historical reason for explosive increases in gold prices is not only the rapid devaluation of money but the total evaporation of confidence in paper money. During such times, gold resumes its age-old role as money. This means that if the world were to lose faith in the dollar for any reason, all roads would lead to gold and silver. But beware: the negative correlation of gold with just about everything else only works in extreme cases.

There are quite a few misunderstandings about this correlation when it comes to gold. First of all, gold and the dollar are almost always negatively correlated. Gold is a commodity, and commodities are traded in dollars. So even if commodity prices fall in dollar terms, when the dollar is rising, commodities can still become more expensive in local currencies.

The dollar usually does well when US interest rates rise, sucking money into US bond markets. To buy US bonds or bonds denominated in US dollars, foreigners also have to buy dollars, which pushes up the price of the greenback. That in itself is mostly bad news for gold, which trades in dollars. More importantly, gold also becomes less attractive as an investment when interest rates rise – especially real interest rates. After all, gold does not yield interest.

Investors are always surprised when I say that the price of gold could well double over the next few years. That would not be the first time in history. Until President Richard Nixon lifted the convertibility of the dollar into gold in August 1971, the gold price was $35 an ounce. Then came a doubling to $70, to $140, to $280, to $560, to $1,120, and recently it almost doubled again to around $2,000 an ounce. If my math is correct, that’s six doublings since I was born. Of course, timing remains a tricky business. And gold, like just about all asset classes, moves in big waves. But we could well be on the cusp of a big wave.

Many countries are trying to diversify their reserves away from the dollar. Gold is also a way to play the growth markets. The biggest physical demand for gold comes from emerging markets. India and China account for half of all demand. If the emerging markets are doing well, you can expect gold to do well too.

If you like gold, you should love silver

Gold has few industrial applications though. The production of smartphones and circuit boards does require a small amount of gold. But unlike zinc, copper or aluminum, gold can hardly be called an industrial raw material.

With an investment in silver, you are betting on two horses: one called precious and another called industry. Silver is at such historically low levels that it is probably the cheapest metal on the planet right now. But again, potential return and risk go hand in hand, as silver and silver mines are still a lot more volatile than their gold counterparts.

This article is adapted from The New World Economy in 5 Trends: Investing in Times of Superinflation, Hyper Innovation & Climate Transition by Koen De Leus and Philippe Gijsels.

This article was written by an external contributor and does not represent the views of MONIIFY. Want to share your opinion with our readers? Pitch your column at opinion@moniify.com