Wong Chew Beng has been brewing coffee at his coffee shop in the Malaysian state of Selangor for more than 30 years.

A lot’s changed in that time, not least of which the cost of a cup, which has nearly tripled from about 1 ringgit (40 cents) in the 1990s for a kopi-o, or black coffee to 3 ringgit today.

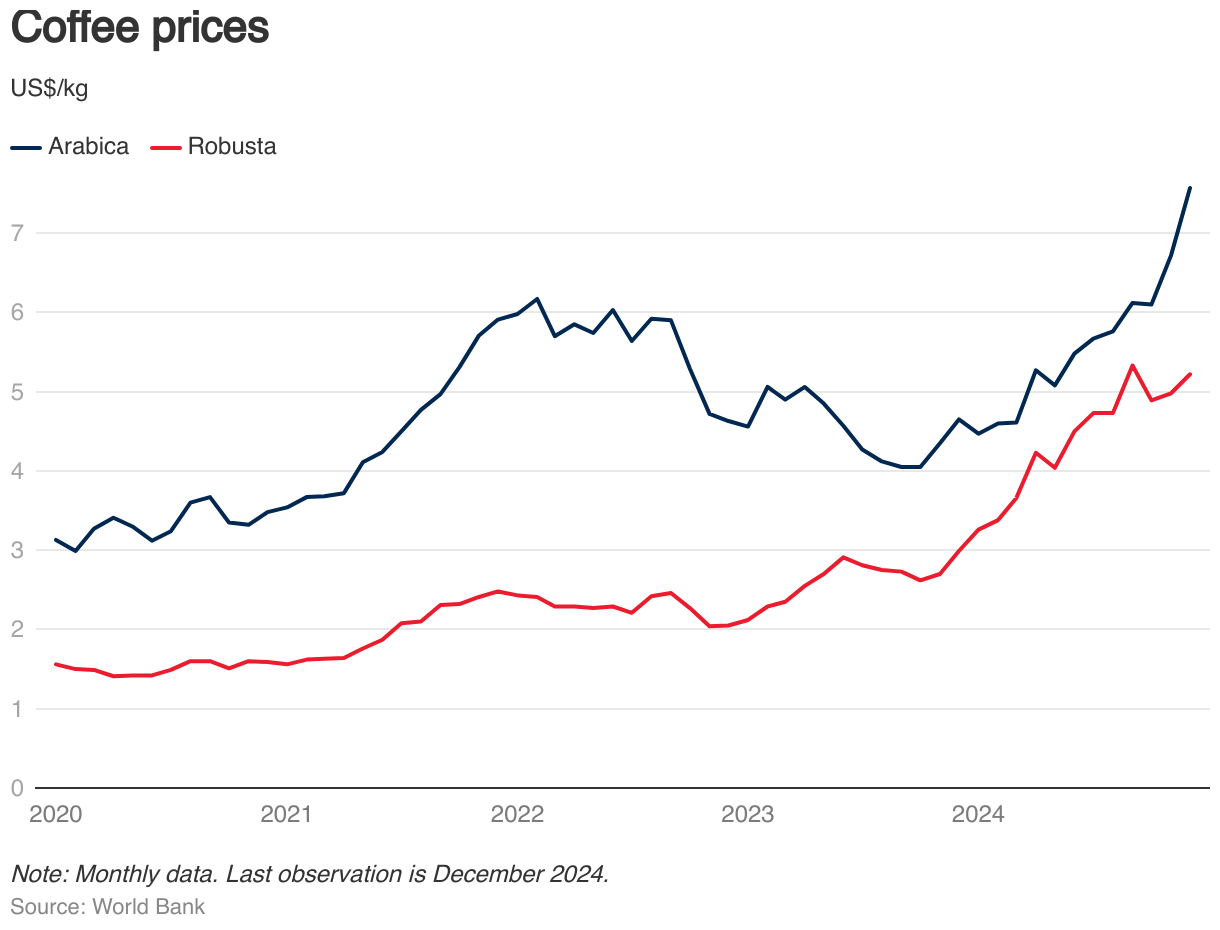

But now the price is about to shoot up even further, increasing the pain for fans of the bitter bean. In January, futures for robusta coffee beans rose above $5,500 per tonne — the highest seen since 2009.

As for Arabica coffee, is it the most popular blend worldwide? That’s currently selling for more than $7,300 per tonne; prices last seen in 1977 when Brazil’s plantations were destroyed by snow.

Demand > Supply

The surging prices are all down to basic economics. Demand is greater than supply right now, says Kelvin Ngow, president of the Malaysia Specialty Coffee Association.

Yields of coffee beans, a climate-sensitive crop, have been lower due to extreme weather conditions like unpredictable rainfall and severe droughts in Brazil and Vietnam, two of the world’s largest producers.

The lack of supply in the market will impact the entire supply chain, Ngow tells MONIIFY. The shortages and high prices are likely to persist until 2026, he adds.

The reduced supply of coffee beans is brewing disaster for lovers of coffee, a cultural institution in Malaysia and neighboring Singapore too. In both countries, kopi, as it’s known, is typically brewed with robusta beans, mixed with other varieties like arabica or liberica and roasted with butter or lard and sugar to bring out the aroma.

Read more: Why cocoa tasted sweeter than Nvidia in 2024

While Malaysia has its own coffee plantations, it only accounts for 0.8% of global production, hardly enough to make a dent in prices.

So, to keep kopi wallet-friendly, small-time roasters like Wong can consolidate their purchases with other operators for leverage in offsetting the price hikes.

It’s not just the independent roasters that are feeling the pinch. Even the world’s biggest roaster Nestle is raising prices and making its coffee bags smaller.

While stocks of coffee-related stocks like Nestle, Starbucks and JDE Peet have been mixed, instruments like the WisdomTree Coffee exchange traded commodity has doubled in price in the past year.

Spill the beans

In the face of climate change, the World Bank is advising farmers to cultivate climate-resilient coffee varieties, improving water management and enhancing soil fertility.

In 2023-24 harvest, Brazil produced around 40% of the world’s coffee beans, or 66.3 million 60-kilogram bags, which is the standard weight used in the international coffee trade, down from 2020’s peak of 69.9 million bags. Vietnam produced less than half of that, or around 28 million bags, of which 95% were robusta beans.

Read more: Gold vs S&P 500: 2024’s heavyweight fight is going down to the wire

While Vietnam’s 2024-25 coffee harvest is expected to yield more than previous years, according to estimates by its Coffee and Cocoa Association, demand may still outstrip supply.

And that demand for the addictive drink is only tipped to keep growing. According to the International Coffee Organization, global coffee consumption is expected to double to 6 billion cups daily by 2050.

For Wong, the growing demand does little to mitigate the pain of rising costs, while keeping his kopi affordable. His solution? Changing the ratio of his local coffee beans with imported beans to strike the right blend for his customers’ wallets.

“Coffee bean prices have gone up and down, but we have our long-time supplier, so we know how to manage these fluctuations,” he says.

Edited by Victor Loh and Tim Hume. If you have any tips, ideas or feedback, please get in touch: talk-to-us@moniify.com